Questions

Questions

How are we intervening in battering and the unique nature of this particular kind of violence against women, characterized by ongoing coercion, control, and violence?

Does our response make people safer? Are we reaching those who are most dangerous and cause the most harm? What messages are we sending and reinforcing? Are we paying attention to how our intervention impacts victims of battering and the community?

Beginning in 2007—after decades of experience in reforming the criminal legal system’s response to domestic violence crimes and exploring “coordinated community response”—St. Paul, Minnesota, asked such questions of itself. [1]Coordinated community response (“CCR”) is the collective act of ensuring that institutions intervening in violence against women (1) centralize safety and well-being for victims/survivors, (2) hold perpetrators accountable while offering opportunities to change, and (3) seek systemic change that contributes to ending violence against women. In 1980, Duluth, MN, began the groundbreaking work to define CCR in the setting of the criminal legal system. See Coordinating Community Responses to Domestic Violence: Lessons from Duluth and Beyond, Melanie F. Shepard and Ellen L. Pence, Eds., Sage Publications, 1999. Praxis International’s founding director, Ellen Pence, was instrumental in developing the CCR idea and approach and drawing upon it in designing the Blueprint for Safety. A partnership of advocates, system practitioners, and a faith-based economic and social justice coalition united to examine whether and how the community was meeting these goals. After using a Safety and Accountability Audit to look deeply at current practice, the partnership sought support from the Minnesota Legislature to create a comprehensive, unified framework that would define how the criminal legal system should respond to domestic violence-related crimes, particularly those involving the greatest harm. The result was the St. Paul Blueprint for Safety, subsequently tailored for broader adaptation by Praxis International as the Blueprint for Safety and drawing on the long history of institutional change provided by the Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (“Duluth Model”).

Blueprint Defined

Blueprint Defined

The Blueprint for Safety (Blueprint) is a coordinated justice system response to domestic violence crimes that positions this complex system to respond more quickly and effectively and enhance its capacity to stop violence, reduce harm, and save lives. While the Blueprint is applicable to the broad range of domestic violence crimes, its primary focus is on the criminal legal system’s response to battering in intimate partner relationships. [2]The Blueprint differentiates battering, characterized by ongoing, patterned coercion, intimidation, and violence; resistive violence, used by victims of battering to resist or defend themselves or others; and non-battering violence resulting from such causes as a physical or mental health condition or traumatic brain injury. The legal system’s category of “domestic violence” includes many types of abusive behavior and relationships. When this guide refers to “domestic violence crimes,” it is primarily concerned with those in the context of battering, although the policies, protocols, and tools included benefit the response to all forms of domestic violence.

its capacity to stop violence, reduce harm, and save lives. While the Blueprint is applicable to the broad range of domestic violence crimes, its primary focus is on the criminal legal system’s response to battering in intimate partner relationships. [2]The Blueprint differentiates battering, characterized by ongoing, patterned coercion, intimidation, and violence; resistive violence, used by victims of battering to resist or defend themselves or others; and non-battering violence resulting from such causes as a physical or mental health condition or traumatic brain injury. The legal system’s category of “domestic violence” includes many types of abusive behavior and relationships. When this guide refers to “domestic violence crimes,” it is primarily concerned with those in the context of battering, although the policies, protocols, and tools included benefit the response to all forms of domestic violence.

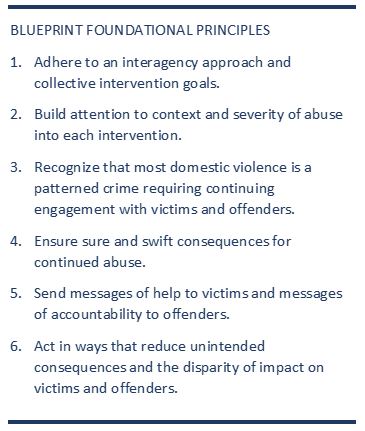

The Blueprint is a distinct blend of approach, document, and process that together fully articulate the idea of a coordinated community response. As an approach, the Blueprint is a shared way of thinking about battering and domestic violence. It gets everyone on the same page under a common understanding of the intimidation and violence that characterize battering and how to intervene most successfully. The Blueprint is also a process for shared problem identification and problem solving based on regular monitoring and adjustments to practice. As a document, the Blueprint is a set of written policies, protocols, and training memos drawn from templates that are based on research and best-known practice. While each agency writes its own policy and protocols, the Blueprint framework and templates connect agencies in a unified, collective policy.

The Blueprint grew from conversations and consultation with victims of battering, community-based advocates, system practitioners, defense attorneys, researchers, agency leaders, other community members, and local and national experts. The Blueprint also grew from a recognition that while there had been many improvements and gains in the criminal legal system’s response to battering, the coordinated community response (CCR) sometimes floundered under the realities of making change in such a complex system. In many communities, the CCR pitfalls could be characterized by:

- An overall drift from the original purpose of CCR to create systemic change that improves outcomes for victims of violence against women and deterrence for abusers

- Reform replaced by meeting for the sake of meeting, with more emphasis on who should come to the table rather than on what should happen once they arrive

- Problem-solving limited to individual cases rather than a focus on systemic problems

- Policy development in a few agencies (e.g., law enforcement or prosecution), but rarely coordinated across all agencies that intervene in domestic violence cases

In St. Paul, the core organizers—the St. Paul Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, St. Paul Police Department, St. Paul City Attorney’s Office, and Praxis International—guided a process that involved ten agencies and multiple victim and advocate discussion groups. This broad effort resulted in the set of comprehensive policies, protocols, and related training memos—the Blueprint as a collective policy—implemented in 2010. St. Paul’s groundbreaking work has continued as it digs deeper into how to sustain a Blueprint community over time, effectively address unintended consequences and disparity of impact for survivors and their communities, and fully actualize the Blueprint’s reshaping of coordinated community response.

In 2011, three additional communities joined St. Paul in adapting the Blueprint for Safety: Duluth, Minnesota; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Shelby County/Memphis, Tennessee. Through an Office on Violence Against Women demonstration initiative, the three communities tested the Blueprint under different local conditions, including Duluth and its decades of experience with coordinated community response. This guide is the result of the experiences and lessons from these four early adapters.

Change

Change

The Blueprint is an innovative approach in its emphasis on self-examination and problem-solving, foundational principles, and the central role for community-based advocacy in its leadership and partnerships. The Blueprint is also grounded in over three decades of community practice, research, and reform related to the criminal legal system’s intervention in domestic violence. The early adapters have been able to initiate or strengthen the following kinds of change in their communities:

- Document and communicate the context of the event and the violence occurring across all points of intervention via a series of linked tools: the Blueprint risk questions, 911 call guides, patrol officer’s report format and checklist, framework for setting bail and conditions of release, and sentencing framework. [3]The Blueprint risk questions: (1) Do you believe he/she will seriously injure or kill you/your children? Why or why not? (2) Is the abuse becoming more frequent? More severe? (3) What is the worst incident or time you were the most frightened?

- Anchor criminal case processing in an emergency-911 response that emphasizes a safety-oriented response and reassurance to callers that 911 is available regardless of the number or nature of prior calls.

- Collect and share more detailed information about who was at the scene and what happened, including improved witness interviews and direct observations by officers.

- Assess first for self-defense in cases where both parties are alleged to have used violence; make a predominant aggressor determination when self-defense cannot be established.

- Make more use of previously undercharged crimes, such as stalking or harassment, terroristic threats, witness tampering, crimes involving children, sexual assault, and burglary.

- Set a foundation for advocacy-initiated response by notifying the community-based advocacy program of domestic violence-related arrests and incidents where the suspect has left the scene. [4]One of the riskiest and most stressful times in a victim’s life is when the criminal justice system gets involved. Early contact with an advocate can lay a foundation for continued support and contribute to victim safety and well-being. When an advocate calls a victim and offers confidential services—which she can refuse—most victims are willing to talk. Under an advocacy-initiated response, the arresting officer contacts the community-based advocacy program to let them know an arrest has been made and lets the victim know that an advocate will be calling. An advocate then calls the victim to offer confidential services related to her immediate safety needs, information about the court process, and determining what she wants to have happen in court and her wishes regarding contact with her partner.

- Strengthen investigation and charging related to suspects who have fled the scene prior to officers arriving.

- Establish a framework for conditions of pretrial release that reflects risk and danger and includes victim input wherever possible.

- Respond to violations of pretrial release and conditions of probation with swift consequences based on graduated sanctions.

- Incorporate risk and danger considerations into prosecutors’ charging decisions, bail recommendations, and negotiated plea agreements.

- Respond to domestic violence crimes in ways that are victim safety-centered but not victim-dependent.

- Position probation agencies to be able to differentiate the context and severity of a particular case and provide sanctions and supervision that best fit the case.

- Provide judges with more detail about the pattern and severity of abuse, including more detail on the type, scope, and severity of abuse.

- Establish internal and interagency monitoring of domestic violence policy and practice,

- Engage more directly with victims and survivors to better meet individual needs related to safety, identify any problems in how interventions impact victims and the community, and keep the criminal legal response grounded in awareness of the unique nature of battering.

- Initiate ways to be proactive in identifying and responding to possible unintended consequences and disparity of impact related to Blueprint policies and practice.

The Blueprint for Safety begins with and is ultimately sustained by forging an identity as a Blueprint community. The qualities of a Blueprint community include: (1) a commitment to the Blueprint foundation principles and purpose; (2) a shared, coherent way of thinking about domestic violence cases and the most effective interventions; (3) a central role for community-based advocacy in Blueprint leadership and partnerships, and (4) a commitment to using the Blueprint’s essential elements as a constant reference point for weathering the inevitable changes in local conditions that occur over time in any community and in a system as complex as the criminal legal system.

Tools

Tools

Is your community ready to design and implement a Blueprint for Safety? This guide will help answer that question. If the answer is “yes,” the guide and related tools will prepare your community to adapt, implement, and sustain the Blueprint: i.e., to become a Blueprint community.

The Quick Start Guide introduces the Blueprint and the roles and activities involved in establishing a Blueprint. It provides a stepping-off point to become familiar with the approach and process and gauge community readiness.

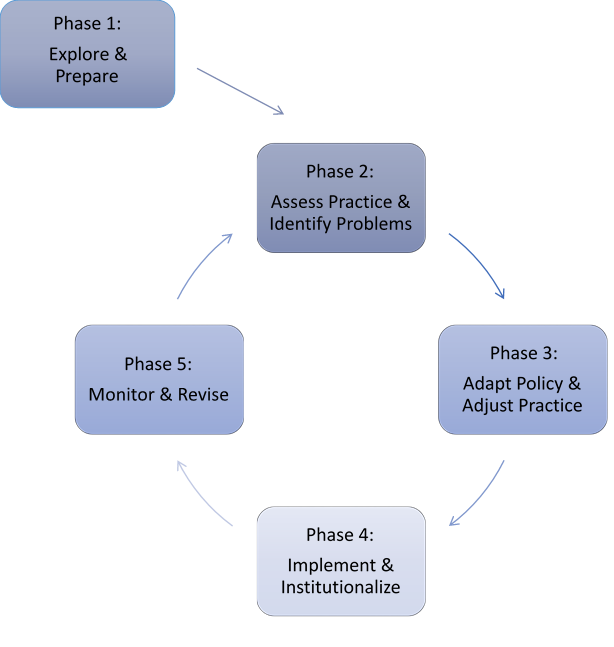

The five sections on Blueprint phases, activities, and tools are the heart of the guide. They include details for what happens, who is involved, and the key tasks, timelines, and tools for each phase in becoming a Blueprint Community. Turn to specific tools as you need them. The sections include:

Phase 1: Explore and Prepare

Secure community will to initiate the development process and establish a Blueprint adaptation team.

Phase 2: Assess Practice and Identify Problems

Conduct an assessment of current policy and practice to identify gaps that the Blueprint will address.

Phase 3: Adapt Policy and Adjust Practice

Use the Blueprint templates to revise and write policies and protocols for each agency and to produce a collective policy.

Phase 4: Implement and Institutionalize

Secure policy approvals, hold a community launch event, conduct internal and interagency training, initiate new documentation and administrative procedures, and establish a process for ongoing monitoring.

Phase 5: Monitor and Revise

Conduct the ongoing data collection and assessment activities necessary to ensure that the Blueprint functions as a “living,” sustainable response to battering and domestic violence crimes.

Principles and Complex Realities frames the particular challenge of realizing two of the Blueprints distinctive foundational principles: Principle 2, to recognize that most domestic violence is patterned crime requiring continuing engagement with victims and offenders; and Principle 6, to act in ways that reduce unintended consequences and the disparity of impact on victims and offenders. This discussion acknowledges that the Blueprint seeks to address three complex realities: (1) the deep and pervasive harm of violence against women, (2) the deep and pervasive harm of mass incarceration and its impact on marginalized communities, and (3) the ways in which victims of battering are routinely caught up in the criminal legal system. The discussion offers strategies and two case studies to illustrate how such tools might be used.

Insights from Early Adapters sums up the major recommendations on how to organize and sustain the Blueprint’s sweeping approach to changing the criminal legal system’s response to battering.

The Appendix includes all of the related tools for each stage of development and others referenced throughout the guide.

This guide rests on lessons from the Blueprint’s early adapters and the decades of criminal legal system reform preceding it. As the work of St. Paul, Duluth, New Orleans, and Shelby County continues—and as additional communities gain experience with the Blueprint’s approach, documents, and process—further revisions and additions to the tools presented here are likely. The Blueprint is meant to be a dynamic and evolving idea as it seeks to stop violence, reduce harm the caused by battering, save lives, and strengthen our communities.

The Blueprint for Safety: Creating and Sustaining a New Practice

The Blueprint for Safety: Creating and Sustaining a New Practice

References

| ↑1 | Coordinated community response (“CCR”) is the collective act of ensuring that institutions intervening in violence against women (1) centralize safety and well-being for victims/survivors, (2) hold perpetrators accountable while offering opportunities to change, and (3) seek systemic change that contributes to ending violence against women. In 1980, Duluth, MN, began the groundbreaking work to define CCR in the setting of the criminal legal system. See Coordinating Community Responses to Domestic Violence: Lessons from Duluth and Beyond, Melanie F. Shepard and Ellen L. Pence, Eds., Sage Publications, 1999. Praxis International’s founding director, Ellen Pence, was instrumental in developing the CCR idea and approach and drawing upon it in designing the Blueprint for Safety. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Blueprint differentiates battering, characterized by ongoing, patterned coercion, intimidation, and violence; resistive violence, used by victims of battering to resist or defend themselves or others; and non-battering violence resulting from such causes as a physical or mental health condition or traumatic brain injury. The legal system’s category of “domestic violence” includes many types of abusive behavior and relationships. When this guide refers to “domestic violence crimes,” it is primarily concerned with those in the context of battering, although the policies, protocols, and tools included benefit the response to all forms of domestic violence. |

| ↑3 | The Blueprint risk questions: (1) Do you believe he/she will seriously injure or kill you/your children? Why or why not? (2) Is the abuse becoming more frequent? More severe? (3) What is the worst incident or time you were the most frightened? |

| ↑4 | One of the riskiest and most stressful times in a victim’s life is when the criminal justice system gets involved. Early contact with an advocate can lay a foundation for continued support and contribute to victim safety and well-being. When an advocate calls a victim and offers confidential services—which she can refuse—most victims are willing to talk. Under an advocacy-initiated response, the arresting officer contacts the community-based advocacy program to let them know an arrest has been made and lets the victim know that an advocate will be calling. An advocate then calls the victim to offer confidential services related to her immediate safety needs, information about the court process, and determining what she wants to have happen in court and her wishes regarding contact with her partner. |