Principle 2: Recognize that most domestic violence is patterned crime requiring continuing engagement with victims and offenders.

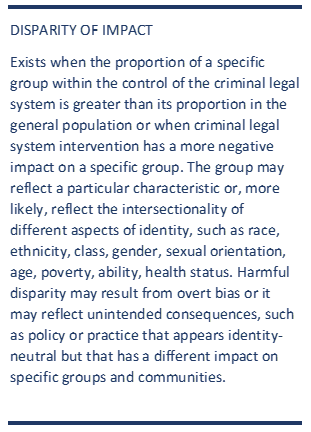

Principle 6: Act in ways that reduce unintended consequences and the disparity of impact on victims and offenders.

Reliance on the criminal legal system to address violence against women has been subject to much debate over the past thirty years, a vigorous debate that continues today. [1]For example, see Safety and Justice for All: Examining the Relationship between the Women’s Antiviolence Movement and the Criminal Legal System, MS. Foundation for Women, 2003, based on meeting report by Shamita Das Dasgupta and summary by Patricia Eng. Also, the positions and publications of INCITE!. The Blueprint for Safety enters this debate by acknowledging and trying to address three complex realities: (1) the deep and pervasive harm of violence against women, (2) the deep and pervasive harm of mass incarceration and its impact on marginalized communities, and (3) the ways in which victims of battering are routinely caught up in the criminal legal system. The criminal legal system becomes involved in battered women’s lives when they reach to it for help; when a family member, friend, or neighbor intervenes; or when women are entrapped or criminalized by their circumstances and survival strategies.

The Blueprint is not a way to force everyone to use the criminal legal system. It endeavors to make that system work in as protective and least harmful and oppressive way as possible for victims of battering who seek it out and for those who are drawn into it. To make that system work in as protective and least oppressive way as possible requires direct attention to issues of disparity.

Problems of Immense Scope and Impact

Problems of Immense Scope and Impact

“. . . A woman called [Police Department] to report a domestic disturbance. By the time the police arrived, the woman’s boyfriend had left. The police looked through the house and saw indications that the boyfriend lived there. When the woman told police that only she and her brother were listed on the home’s occupancy permit, the officer placed the woman under arrest for the permit violation and she was jailed. In another instance, after a woman called police to report a domestic disturbance and was given a summons for an occupancy permit violation, she said, according to the officer’s report, that she “hated the [Police Department] and will never call again, even if she is being killed.”

[2]U.S. Department of Justice, Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, p. 81. Released March 4, 2015.

Susan and her boyfriend, Robert, are a young African American couple. Both are twenty years old; they live together with their six-month-old daughter, June. Susan has an early morning shift at a coffee shop and Robert recently started night classes to become a medical technician. Two months ago, neighbors called police when they heard Susan screaming. Robert was arrested for misdemeanor assault, even though Susan asked that they not arrest him. She told police that she had screamed at Robert after he had slapped her and broken several plates and that she also slapped him back. He had hit her a couple of times after they first got together, she told police, but this was the first time in over a year. Robert was booked into the jail for two days until his brother could pay the bail. He was released and ordered to have no contact with Susan. Susan missed two days of work when Robert was in jail because there was no one to care for June. When Robert called to apologize, she asked him to return home. Ten days later, while giving her a ride to work, Robert is stopped for having expired plates. Because there is a no-contact order, Robert is arrested, his car impounded, and Susan and their daughter are left at a bus stop. Robert is charged with a gross misdemeanor for violating the no-contact order, in addition to the original assault charge. He’s released and again ordered to have no contact with Susan. Now he has no car or money to pay the impound fee and get his car back; the fee grows by forty dollars a day. Susan has no one to care for June. Her boss asks her to get back on her usual shift or quit. Robert has missed several days of classes and a major test. Neither of them can get to work or school without traveling by bus for over an hour each way, but Susan could take the first bus at 4:30 am if Robert was there for June. If Robert returns home, however, he risks being charged with a felony for violating the no-contact order a second time.

Such stories raise our opening questions: How are we intervening… Does our response make people safer? Are we reaching those who are most dangerous and cause the most harm? What messages are we sending and reinforcing? Are we paying attention to how our intervention impacts victims of battering and the community?

The Blueprint for Safety has emerged during a time of widespread national discussion about racial and class disparities in the criminal legal system. Many activists, communities, and public officials are examining how to address the broad and costly impact of a process that incarcerates the highest number of people in the world, feeds a prison system of unprecedented size, and brings millions of people under an often lifetime sentence of restricted access to housing, employment, education, and voting rights. [3]The United States has less than 5% of the world’s population but over 23% of the world’s incarcerated people. It imprisons the most women in the world. Crime rates do not account for the high incarceration rates. US Rates of Incarceration: A Global Perspective, Christopher Harvey, National Council on Crime and Delinquency, November 2006. See also: Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Prison Policy Initiative Briefing, March 12, 2014. Incarceration rates for Black, Latino, and Native American peoples are hugely disproportionate to their populations. [4] Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity, Leah Sakala, Prison Policy Initiative, May 28, 2014. This “mass incarceration” comes at a high cost: 70 billion dollars each year to incarcerate 2.2 million people, plus 65 million adults (approximately one in four) with a criminal record and its collateral consequences. [5] Criminal Justice in the 21st Century: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System, Conference Report by Tanya E. Coke, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 2013. For a discussion of mass incarceration, see The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander, The New Press, 2010.

Never before have so many been arrested for so little… Despite the minor nature of most offenses processed through the system, a large number of defendants will be too poor to post bail, will plead guilty to time served to get out of jail, and then will suffer one or more of the collateral consequences of criminal conviction: deportation from the United States, the inability to get or keep a job, the loss of housing, student loan disqualification, and/or the denial of the right to vote. [6] New York State Supreme Court Justice Marcy Friedman, Criminal Justice in the 21st Century, p. 8.

Women who are being or have been battered experience this complex, troubled system in many different ways. Their experiences are shaped by different social realities and intersections of race, ethnicity, class, age, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, ability, community, history, oppression, privilege, and many other aspects of culture and identity.

Women are disproportionately impacted by intimate partner violence, rape, and stalking. Many experience high lifetime rates of severe violence and the violence contributes to or causes unemployment, homelessness, and loss of their children. Violence against women and girls also increases the risk of arrest and incarceration, particularly for women of color and poor women. Criminalization of women’s survival strategies and entrapment into crime by their abusive partners and by gender, race, and class oppression are paths to incarceration. Once criminalized and under correctional control, women face state “enforcement violence” through coercive laws and policies. [7] Women’s Experiences of Abuse as a Risk Factor for Incarceration, Mary E. Gilfus, VAWNet Applied Research Forum, December 2002. Gilfus references the following researchers: Meda Chesney-Lind and Noelie Rodriguez (criminalization of survival strategies), Beth E. Richie (gender entrapment), and Anannya Bhattacharjee (enforcement violence). The consequences of enforcement violence, in turn, often lead to unemployment, homelessness, and loss of their children.

Women are disproportionately impacted by intimate partner violence, rape, and stalking. Many experience high lifetime rates of severe violence and the violence contributes to or causes unemployment, homelessness, and loss of their children. Violence against women and girls also increases the risk of arrest and incarceration, particularly for women of color and poor women. Criminalization of women’s survival strategies and entrapment into crime by their abusive partners and by gender, race, and class oppression are paths to incarceration. Once criminalized and under correctional control, women face state “enforcement violence” through coercive laws and policies. [7] Women’s Experiences of Abuse as a Risk Factor for Incarceration, Mary E. Gilfus, VAWNet Applied Research Forum, December 2002. Gilfus references the following researchers: Meda Chesney-Lind and Noelie Rodriguez (criminalization of survival strategies), Beth E. Richie (gender entrapment), and Anannya Bhattacharjee (enforcement violence). The consequences of enforcement violence, in turn, often lead to unemployment, homelessness, and loss of their children.

The United States imprisons more women than any country in the world and most of those women are survivors of violence. Over a million women are in the correctional population. [8] Lauren E. Glaze and Danielle Kaeble, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, December 2014. The correctional population includes those on probation or parole, in state or federal prison, or in local jail. Between 1980 and 2010, the rate of growth of women in prison exceeded the rate of increase for men (646% to 419%). While incarceration rates overall have declined somewhat since 2008, the rate of women’s incarceration continues to outpace the rate for men. [9]Marc Mauer, The Changing Racial Dynamics of Women’s Incarceration, The Sentencing Project, February 2013.

Most women in the correctional system have histories of being abused, either as a child and/or as an adult. Estimates of prior abuse range from 55% to as high as 95%. Lower estimates reflect general screening questions while more in-depth studies with expanded measures of abuse report that nearly all girls and women in prison have experienced physical and sexual abuse throughout their lives. [10]For a review of research studies, see Gilfus, Women’s Experiences of Abuse as a Risk Factor for Incarceration (at note 150). Severe physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner is an overwhelmingly common experience of incarcerated women: 75% to 93% of women who report prior abuse have been abused by an intimate partner. [11]Studies cited in About Survivors in Prison, fact sheet published by Domestic Violence Survivors’ Justice Act.

Women in the correctional system are disproportionately women of color. While the rate at which African American women are incarcerated in comparison to white women and Latinas has dropped in the past ten years, African American women still represent over 30% of incarcerated women and Latinas represent roughly 17%. [12]Mauer, Changing Racial Dynamics. “Changes during the decade were most pronounced among women, with black women experiencing a decline of 30.7% in their rate of incarceration, white women a 47.1% rise, and Hispanic women a 23.3% rise” (p. 7-8). While the downward trend for African American women is encouraging, as one commentator put it, “I don’t want to just exchange women of color for poor white women.” [13]Glenn Martin, Fortune Society, cited in “Race, Women and Prison,” Graham Kates, The Crime Report, February 28, 2013. Data on rates of incarceration for Native women is less accessible but rates for Native women have been rising—often greater than rates for Native men—and vastly outpace those for whites. For example, in South Dakota Native peoples are 10% of the population but Native women make up 35% of prison inmates; in Montana, Native peoples are 6.8% of the population but 29.6% of women prisoners. [14]Frank Smith, Incarceration of Native Americans and Private Prisons.

To repeat, the Blueprint for Safety faces three complex realities as it seeks to change the criminal legal system response to battering: (1) the deep and pervasive harm of violence against women, (2) the deep and pervasive harm of mass incarceration and its impact on marginalized communities, and (3) the ways in which victims of battering are routinely caught up in the criminal legal system. The realities are interconnected.

- Mass incarceration and the hyper-surveillance of the criminal legal system in marginalized communities is a barrier to engagement. Victims of battering who feel “over-policed and under-protected” in their communities and daily lives are unlikely to see the police and other representatives of the criminal system as a trusted source of help. [15]For example, see the papers published in conjunction with the 2012 UCLA Law Review Symposium, Overpoliced and Underprotected: Women, Race, and Criminalization. See also, Donna Coker, et al., Why Opposing Hyper-Incarceration Should be Central to the Work of the Anti-Domestic Violence Movement, University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review, 2015.

- Battered women can become even more isolated in an environment of mass incarceration and over-policing as they are pushed to choose between their individual well-being and safety and the increasing devastation to their families and communities by the immediate and collateral consequences of incarceration.

- Violence against women—and battering, specifically—is a pathway to incarceration and state control for millions of women, a pathway that has opened even wider with the well-intended reforms of mandatory arrest and prosecution for domestic violence-related crimes.

How does a Blueprint community address these complex realities? How does the focused, interagency collective policy prescribed by the Blueprint for Safety make meaningful change in the face of these realities? How does a community make two of the Blueprint’s most distinctive principles real?

Questions and Lessons

Questions and Lessons

The Blueprint for Safety begins to embody its principles and address these complex realities in part by asking many questions. Some of these questions focus narrowly on a specific practice or aspect of intervention; others are broader and more philosophical in nature.

To address and ultimately reduce harmful interventions and disparity of impact is challenging, arduous, and essential work. Few CCRs have been positioned to initiate and sustain an examination and response to disparity in their communities. The CCR idea and practice has been largely dominated by a criminal legal system orientation that has more or less accepted business as usual, even sometimes framing its role as “getting the bad guys.” For many victims of battering in marginalized, underserved and over-scrutinized communities, interventions based on accepting the system as-is have not contributed to safety, well-being, or accountability.

The Blueprint is distinctive in defining action to reduce harmful intervention and disparity as an essential function of a coordinated response to battering. That work begins by posing the questions to be answered, both as suggested below and as specific to each community. Lessons from the early Blueprint adapters—the demonstration communities and St. Paul—point the way to strategies that move this critical work forward.

In its structure and organization, the Blueprint requires a commitment by community-based advocates and allies in the criminal legal system to “stay at the table” as they identify problems and explore solutions. It is difficult to take varied viewpoints about complex issues—particularly when related to race, gender, class, and other disparities—and secure agreement on a direction to take, let alone agree on specific policy and practice changes. It is difficult to challenge long-standing practice.

Among the more specific questions that a Blueprint community must ask:

- How do practitioners sort out battering from other kinds of domestic violence? How can they use the Blueprint risk questions a path to identify battering and find out more clearly who is most dangerous to whom?

- Are there ways in which 911 is used as a resource by the community that inadvertently contributes to disparity?

- What is the impact of poor guidance on how to make sound self-defense determinations and how to assess for predominant aggressor when warranted?

- What domestic violence-related crimes should be enhanced? What is the impact of expanding the category of felony crimes related to domestic violence?

- Should prosecution diversion be reconsidered as an option in domestic violence-related crimes? Under what conditions and with what safeguards?

- What is the impact of the following kinds of laws and practices in relation to engagement and to a fair and just response: mandatory minimum sentencing, penalty/sentencing enhancements, mandatory arrest, and mandatory no-contact orders?

- How might options and costs related to electronic monitoring—or lack of options—contribute to disparity of impact?

- How can sanctions account for people’s economic circumstances (i.e., fees, fines, forfeitures and conditions under which they are leveled and multiplied)?

- At each step in the system, do people receive clear information about what is expected of them? Is there confirmation that people in fact understand what is expected? Are supports and resources in place to support their success in meeting what’s expected?

- In what ways might probation sanctions for technical violations (i.e., unrelated to a new assault or crime) contribute to disparity of impact?

- Should there be any kind of way to expunge criminal records in domestic violence-related convictions? If so, under what circumstances?

Among the broader questions:

- How do we keep women and children safe and yet hold batterers accountable without necessarily seeking longer, more punitive sentences as the response?

- How do we meet the needs of victims without eroding judicial fairness and the due process protections of accused persons?

- Who belongs in jail and when? Who does not belong in jail?

- What is the multiplier effect of intensive policing and poverty? Which communities reflect the greatest disparity in rates of incarceration and state control?

- What are effective alternatives for women and children’s safety within the criminal legal system?

- What discretion should exist for practitioners at each phase of the criminal legal system process?

- Would reducing the role of law enforcement provide a convenient excuse for some law enforcement officials to return to a response where victims of battering were largely ignored or discounted?

- How might we build a framework of community safety outside of criminal legal system? Should the criminal legal system become the diversionary program, the secondary option? If so, how?

- What are the right interventions to maximize safety and accountability while minimizing unintended harm and disparity?

- How can we put the intersection of poverty and race at the forefront of discussions and policy-making rather than treat it as an afterthought?

BUT . . . We can hear you wonder: how can it be helpful in an adaptation guide to pose so many questions? A guide should have the answers, right?

Not every question can be asked and answered at once. Initial answers might prove misguided when actually implemented or upon closer attention to unintended consequences. Nonetheless, the experiences of the early Blueprint adapters suggest effective strategies to accomplish both the mechanics of working together and the kinds of change that contribute to reducing harmful consequences and disparity. For example, the following discussion of strategies illustrates how two Blueprint communities have investigated disparities related to the arrests of victims of battering and the impact of mandatory universal no-contact orders.

The Blueprint for Safety is a dynamic approach and process to shaping the criminal legal system’s response to battering. It is not a one-time event or document to place on a shelf. The Blueprint is very much a work in progress. As it is adapted and practiced by more communities, broader implementation will produce new insights and answers on how the criminal legal system can best engage with those impacted by battering and intervene in ways that are protective and effective while reducing unintended consequences and disparity of impact. Domestic violence-related crimes are a significant part of the business of the criminal legal system. As the Blueprint principles shape actions in that system they have the potential to reduce broader institutional harm and disparity.

Strategies

Strategies

On their own, Blueprint organizers and leaders are poorly positioned to tackle the deep-seated, structural factors that contribute to overall disparity—such as poverty and a highly racialized society. The overwhelming scope of the problem can make any effort appear impossible. Within the sphere of domestic violence-related crimes, however, a Blueprint community can investigate and make concrete changes in the response that help avoid harmful consequences and help reduce aspects of disparity.

Strategies will evolve as more communities implement the Blueprint and contribute their experiences. Again, the Blueprint is meant to be a “living” application of principles and practice. Its various tools and templates, such as those presented in this guide, will be revised to reflect new knowledge about how to best discover, talk about, and address the complex issues of disparity. In the meantime, the available tools help a Blueprint community conduct focused and effective inquiries into aspects of disparity and produce concrete recommendations for change.

Tool Box

Tool Box

This adaptation guide itself is a primary tool via its organization of planning, implementation, and monitoring activities, all of which keep the Blueprint principles in focus. In addition, the following specific approaches and strategies help keep the Blueprint attentive to disparity.

- Use the practice assessment tools and process to identify possible areas of disparity and harmful intervention. Key assessment tools include:

- Basic data collection about the number and disposition of cases, broken down by gender, race, ethnicity, and other characteristics

- Mapping each step of criminal case processing and examining how disparity might be introduced or magnified

- Consultation with victims/survivors and community members—via interviews and discussion groups, among other strategies—including advocates working with specific populations, to identify problems related to unintended consequences and disparity

- Analysis of forms that direct practitioners to take certain actions (e.g., domestic violence supplement form or bail screening checklist) and the case records that convey the official accounts of cases (e.g., police reports or prosecution files).

- In all Blueprint phases, include meaningful representation (i.e., more than one or two individuals expected to represent an entire community) from communities most affected by likely problem(s) of disparity.

- Build a knowledge base about the nature of disparity within the larger community and the criminal legal system, with attention to the histories and distinctive experiences of people most impacted.

- Use the following questions to shape the exploration of a possible disparity:

- What is the nature of the disparity and how did it come about?

- Who does the disparity impact and in what ways?

- What information is needed in order to define and explore this issue?

- Are there laws that affect the disparity?

- Are there policies or procedures that affect the disparity?

- Are there linkages between intervening agencies—or lack thereof—that affect the disparity?

- Are there Blueprint principles that are not being fully incorporated into a community’s practice that affect the disparity (e.g., incorporation of risk and danger or recognition that risk change can change over time and the response may need to be modified)?

Case Study: New Orleans

Case Study: New Orleans

The New Orleans Blueprint demonstration site analyzed police arrest data and discovered that African American women had the highest rate of arrest among women charged with domestic violence, while also being the most likely to experience intimate partner violence. It began to examine how criminal justice policies and procedures might have a disparate impact on African American women arrested on domestic violence charges.

New Orleans conducted a literature review, analyzed police reports, held advocate and survivor focus groups, and established a community-based Disparate Impact Strategic Planning Committee—known as the disparity impact committee—to guide the Blueprint. The disparate impact committee is grounded in the critical expertise of community members with years of experience working with African American women in New Orleans. The committee also includes Blueprint coordinators, system practitioners, and a university-based researcher who has initiated an expanded analysis of police patrol reports.

Among the themes and discoveries:

- Persistent stereotypes build what Melissa Harris-Perry calls the “Black women’s crooked room” and influence how they are seen in the world. [16]Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, Yale University Press, 2011. The New Orleans Blueprint sought out the Anna Julia Cooper Project on Gender, Race, and Politics in the South as a community partner. It utilized Harris-Perry’s analysis and conceptual framework for understanding the dominant myths about African American women. This includes the “Sapphire” or “angry black woman” who is aggressive, strong, and loud: i.e., therefore cannot be a victim. In the police response, such assumptions can prevail in the absence of thorough self-defense and predominant aggressor determinations.

- African American women turn to the police as a last resort when they are fearful for their own or their children’s safety. This contrasts with the “mad day” belief expressed by police officers in mapping activities, interviews, and analysis of reports: i.e., women are out of sorts with their partners and decide to get mad and call the police.

- Trust is a significant element in whether and how women approach or avoid the police and other agencies. When women report helpful interactions with police and others in the system, it is often because there is an individual “gate-keeper” whom they trust and who acts on their behalf. While such a personal response is useful to an individual woman, it is not institutionalized in a way that benefits all victims of battering.

While the disparity work in New Orleans is ongoing, it has already led to policy changes in the New Orleans Police Department’s approach to self-defense and predominant aggressor determinations, stronger attention to and documentation of the context and history of violence, and plans to revise report formats to eliminate the use of standard modus operandi categories (e.g., “broad nose,” “flabby,” “angry”) that can reinforce stereotypes of African American women.

The New Orleans experience has also produced insights into strategies for organizing community focus groups and adapting risk questions to meet diverse literacy and comprehension levels. For example, building relationships with diverse community-based advocacy organizations—beyond those typically identified as working with victims of domestic violence—was critical to reaching a broader range of participants, particularly those who were reluctant to turn to the police for help. In New Orleans, those relationships included organizations whose primary advocacy focused on issues of poverty, health and wellness, and the lives of marginalized women. The New Orleans analysis also noticed how seemingly neutral elements in Blueprint templates (e.g., document emotional demeanor, physical appearance, and indications of drug or alcohol abuse) can inadvertently reinforce stereotypes of African American women.

Case Study: St. Paul

Case Study: St. Paul

In St. Paul, the defense bar and probation officers raised concerns that young men of color were disproportionately affected by St. Paul’s application of Minnesota state law permitting courts to issue a pretrial or post-conviction Domestic Abuse No-Contact Order (DANCO). The DANCO is enforceable by warrantless arrest and punishable as a misdemeanor. Subsequent arrests for violating the no-contact order, however, can be enhanced as felony-level crimes. There is the possibility that a defendant can commit a low-level misdemeanor assault, be subject to the terms of a DANCO that the victim of the assault may not want, and subsequently be prosecuted as a felon, even if the victim wants contact and no further violence occurs. The defense and probation raise the concern that DANCO enforcement has a disproportionate impact on young men of color, resulting in felony convictions and potential incarceration for violations of no-contact orders that do not involve new acts of violence.

The St. Paul Blueprint partners—including the community-based advocacy program, practitioners, and technical assistance partner, Praxis International—together with the Domestic Violence Coordinating Council, identified the following key questions to answer in order to establish whether and to what extent the perceived disparity exists and how to address the disparity if it is established:

- How many offenders are ending up with felony convictions when they did not commit more violence? What is their race and age? How many did or did not commit additional violence or pose a serious threat to the victim?

- Are convictions for DANCO violations driven by a goal of increased conviction rates or a goal of increased safety?

- Prosecutors have charging discretion; under what circumstances would the Blueprint recommend that prosecutors not issue an enhanced charge for a DANCO violation?

- Under what circumstances should a prosecutor request a DANCO over the objection of a victim during the pretrial period? Post-conviction? What tool should be used to make this determination?

- Should a victim be able to request cancellation or modification of a DANCO? What process could be created to allow cancellation or modification? What tool would the court use to weigh its decision?

- If a cancellation or modification process is established, are advocates prepared to stand with the judicial decision-maker if a woman gets killed after a DANCO is cancelled or modified as she requested?

Initial steps have included (1) information-gathering focus groups with women who have had DANCOs ordered against their wishes, (2) formation of a work group that will draft a process for victim-directed modification or cancellation of no-contact orders, and (3) revisions to prosecutors’ practice so mandatory universal DANCOs are no longer routine. Future steps include (4) case reviews to determine how many offenders are being charged with DANCO violations unrelated to new acts of violence and to examine more closely the risk to victims in such cases, and (5) additional statistical research on felony charges and convictions related to no-contact order violations.

References

| ↑1 | For example, see Safety and Justice for All: Examining the Relationship between the Women’s Antiviolence Movement and the Criminal Legal System, MS. Foundation for Women, 2003, based on meeting report by Shamita Das Dasgupta and summary by Patricia Eng. Also, the positions and publications of INCITE!. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | U.S. Department of Justice, Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, p. 81. Released March 4, 2015. |

| ↑3 | The United States has less than 5% of the world’s population but over 23% of the world’s incarcerated people. It imprisons the most women in the world. Crime rates do not account for the high incarceration rates. US Rates of Incarceration: A Global Perspective, Christopher Harvey, National Council on Crime and Delinquency, November 2006. See also: Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, Prison Policy Initiative Briefing, March 12, 2014. |

| ↑4 | Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity, Leah Sakala, Prison Policy Initiative, May 28, 2014. |

| ↑5 | Criminal Justice in the 21st Century: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System, Conference Report by Tanya E. Coke, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, 2013. For a discussion of mass incarceration, see The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander, The New Press, 2010. |

| ↑6 | New York State Supreme Court Justice Marcy Friedman, Criminal Justice in the 21st Century, p. 8. |

| ↑7 | Women’s Experiences of Abuse as a Risk Factor for Incarceration, Mary E. Gilfus, VAWNet Applied Research Forum, December 2002. Gilfus references the following researchers: Meda Chesney-Lind and Noelie Rodriguez (criminalization of survival strategies), Beth E. Richie (gender entrapment), and Anannya Bhattacharjee (enforcement violence). |

| ↑8 | Lauren E. Glaze and Danielle Kaeble, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, December 2014. The correctional population includes those on probation or parole, in state or federal prison, or in local jail. |

| ↑9 | Marc Mauer, The Changing Racial Dynamics of Women’s Incarceration, The Sentencing Project, February 2013. |

| ↑10 | For a review of research studies, see Gilfus, Women’s Experiences of Abuse as a Risk Factor for Incarceration (at note 150). |

| ↑11 | Studies cited in About Survivors in Prison, fact sheet published by Domestic Violence Survivors’ Justice Act. |

| ↑12 | Mauer, Changing Racial Dynamics. “Changes during the decade were most pronounced among women, with black women experiencing a decline of 30.7% in their rate of incarceration, white women a 47.1% rise, and Hispanic women a 23.3% rise” (p. 7-8). |

| ↑13 | Glenn Martin, Fortune Society, cited in “Race, Women and Prison,” Graham Kates, The Crime Report, February 28, 2013. |

| ↑14 | Frank Smith, Incarceration of Native Americans and Private Prisons. |

| ↑15 | For example, see the papers published in conjunction with the 2012 UCLA Law Review Symposium, Overpoliced and Underprotected: Women, Race, and Criminalization. See also, Donna Coker, et al., Why Opposing Hyper-Incarceration Should be Central to the Work of the Anti-Domestic Violence Movement, University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review, 2015. |

| ↑16 | Melissa Harris-Perry, Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, Yale University Press, 2011. The New Orleans Blueprint sought out the Anna Julia Cooper Project on Gender, Race, and Politics in the South as a community partner. It utilized Harris-Perry’s analysis and conceptual framework for understanding the dominant myths about African American women. |