Change Seeker: Making Institutions Work for People

E-Newsletter for Analyzing Institutional Responses to Violence Against Women

Issue 2

Praxis training and technical assistance on institutional analysis provides tools for advocates and communities to reform the social institutions that respond to victims of violence against women. Change Seeker: Making Institutions Work for People is a bi-annual e-newsletter that features foundations of Institutional Analysis, recent projects, new tools, answers to TA questions, upcoming training events, and interesting applications. We hope it helps you to succeed in your system reform efforts!

Institutional Analysis: Strong Roots in Social Justice*

Community Spotlight: Grand Rapids, Minnesota

Tool Highlights!

Dear Praxis: Who conducts a Safety and Accountability Audit?

Distinctive applications

Institutional Ethnography: Nursing Work and Hospital Reform

Institutional Ethnography: Nursing Work and Hospital Reform

Tracing artists’ work in Canada’s textually mediated art world

Tracing artists’ work in Canada’s textually mediated art world

Institutional ethnography and activism

Institutional ethnography and activism

Institutional Analysis: Strong Roots in Social Justice

Praxis Institutional Analysis (IA) method focuses on reorganizing the way workers are coordinated to process cases to improve outcomes for people. IA gives communities a roadmap for changing the conditions that underpin, for example, violence against women, and provides a framework to close the gaps between what victims of violence need and what the official response provides. But this process wasn’t developed out of the blue and its history is important to understanding how it’s meant to support communities in pursuits of social justice.

In the early 90s, Ellen Pence, founding director of Praxis International, set out to find a way for institutions and communities to be more responsive to victims of violence against women. Reform efforts that focused on training individual practitioners to think differently about cases involving crimes of violence against women was limited in its impact. Most people left a training, went back to work, and while perhaps they felt more compassion for victims, they basically did their work the same way as before. Attributing poor outcomes for victims to the attitudes, personal beliefs, biases, or ignorance of individual workers leaves unchallenged and unchanged the various ways that institutions manage cases in such as way does not adequately connect the intervention to what is actually going on in people’s lives.

Dorothy Smith’s Institutional Ethnography (IE), a sociology for the people, offered Ellen a framework for how to approach local domestic violence reform efforts in Duluth, MN. Dorothy developed IE for activists and researchers to better understand how institutions influence and contribute to society and to strengthen their pursuits of social justice. IE seeks to identify how institutions, systems, and society shape, for example, the single mother’s experiences of her life. As such, IE was the approach Ellen sought to reform the criminal legal system to be more responsive to cases of battering.

Institutional Ethnography (IE), a sociology for the people, offered Ellen a framework for how to approach local domestic violence reform efforts in Duluth, MN. Dorothy developed IE for activists and researchers to better understand how institutions influence and contribute to society and to strengthen their pursuits of social justice. IE seeks to identify how institutions, systems, and society shape, for example, the single mother’s experiences of her life. As such, IE was the approach Ellen sought to reform the criminal legal system to be more responsive to cases of battering.

Through her studies with Dorothy in the mid-1990s, Ellen’s dissertation Safety for Battered Women in a Textually Mediated Legal System (unpublished) became the Safety and Accountability Audit, first used in Duluth to assess how pre-sentence investigations were conducted in domestic violence related-cases. Ellen then established Praxis in 1997 to support communities to implement Safety Audits. The backbone of what we now refer to as Praxis Institutional Analysis (IA), the method has since been applied to issues beyond domestic violence and beyond the criminal legal system. Over 100 projects across the U.S. have used the method to assess a range of institutional responses to a variety of issues. And 17 projects are currently in progress. IA has also been applied internationally, including: Canada (violence against people with disabilities), Australia (criminal justice, child protection, and advocacy), and England (admissions process for community-based advocacy program). IE and IA have contributed to a powerful shift in how we think about and approach institutional reform, thanks to Ellen and thanks to her teacher Dorothy Smith.

Praxis staff and our IA learning community have had the privilege of continued teaching by Dorothy to further develop the method. From 1999 to 2002, Dorothy provided crucial guidance to Praxis and a team of community researchers who conducted a community-based analysis of Indigenous battered women’s experiences with the U.S. criminal and civil justice systems. Dorothy trained the research team, and guided the blending of Indigenous research methods with IE to stay grounded in Indigenous women’s experiences. Also in the early 2000s, Dorothy conducted a series of retreats with Praxis to deepen the way IA focuses on the central role of “texts” in institutional case processing, and offered techniques to analyze those texts to reveal potential points of change. Several years later, Dorothy reviewed and edited Text Analysis as a Tool for a Coordinated Community Response: Keeping Safety for Battered Women and their Children at the Center, a guide that grew out of those retreats. Most recently, Praxis staff participated in a workshop led by Dorothy at the 2015 Society for the Study of Social Problems Annual Meeting in Chicago. And we look forward to learning more from her this summer, now 92 years old, at this year’s Society for the Study of Social Problems Annual Meeting in Montreal, Canada. We are eternally grateful to Dorothy for continuing to guide us and help advance our work.

Community Spotlight: Wellstone Family Safety Program, Grand Rapids, Minnesota

Community Spotlight: Wellstone Family Safety Program, Grand Rapids, Minnesota

A Praxis Safety and Accountability Audit brings together people from different community systems in a process to question and reflect on how their work strengthens or diminishes safety for victims of violence against women. It is a courageous step for participating agencies to be involved and open their practices to the scrutiny of community partners and other practitioners, as well as individuals from outside their community. A willing and capable team is assembled to talk with people, observe work, read case files, and make sense of all the resulting information. It is an opportunity for practitioners in different systems to step back from their usual day-to-day experiences and try to see work practices from the perspectives of victims.

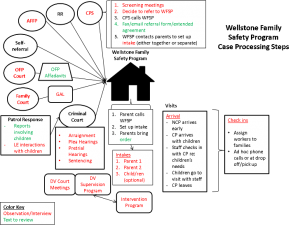

Advocates for Family Peace (AFFP) in Grand Rapids, Minnesota has lead their community through several Safety Audits to assess and enhance their community’s response to domestic violence. In 2016, AFFP used the Safety Audit to assess one of their own programs – the Wellstone Family Safety Program (WFSP) – which provides supervised visitation and exchange services that focus on the safety needs of both adult and child victims of battering. In the early 2000s, AFFP adopted new Office on Violence Against Women guiding principles, policies, and practices that were developed to account for the safety needs of battered mothers and their children. Ten years later, with recent staff turnover and leadership changes, program staff wanted to explore: Why are we doing things the way we are doing them? Is there more we could be doing to keep battered mothers and their children safe? Are there ways for us to hold offenders accountable for continued efforts to harm? Building on previous Audits (which focused on how various other community agencies attended to risk and danger in battering cases), the WFSP Audit Team decided to explore this audit question:

How does Wellstone Family Safety Program assess, document, respond to, and share information related to risk and danger in battering cases?

With support from Praxis, AFFP and WFSP recruited and trained a 9-member team and completed their Audit in just six months. Team members included representatives from Itasca County Probation, Grand Rapids Police Department, Itasca County Health and Human Services-Child Protective Services, Bridges Kindship Mentoring, and staff of WFSP and AFFP. The team gathered information through the following activities:

- Mapping of how families come to WFSP.

- Conversations with battered mothers who utilized or could have utilized WFSP.

- Group interviews of WFSP staff and child protection staff.

Individual interviews with judges, Guardians Ad Litem, AFFP/WFSP reception staff, child protection staff, and probation officers

- Observations, including WFSP intake, child protection screening meetings, Child Justice Initiative monthly meeting, Domestic Violence Court meeting, and supervised exchanges.

- Text review of WFSP case files (signed releases, phone logs, visit log, intervention reports, child refusal reports) and other key documents, when available (affidavit and petition for orders for protection, emergency orders-for-protection, amended orders-for-protection, police reports, divorce orders, etc.). In addition, Praxis conducted an in-depth analysis of case files.

The team has now begun working on implementing changes to close the gaps identified through the audit, including:

| Gaps | Changes | |||

| 1. WFSP receives limited information related to risk and danger prior to and while providing services (from courts, child protection, guardians ad litem, self-referrals, intake assessments) | WFSP has developed a draft domestic violence risk assessment to be conducted during intake with family members. | |||

| 2. A lack of formal ongoing communication with battered mothers and with referral sources compromises WFSP’s ability to adjust to changes in risk and danger dynamics. | WFSP and Itasca County Probation are now in more regular communication. | |||

| 3. WFSP is compromised in holding offenders accountable for dangerous behavior exhibited before, during, and after supervised visits or exchanges. | WFSP now proactively gathers background information and documentation (court orders, affidavits, etc.) to better inform their services. | |||

| 4. WFSP should explore ways to enhance physical security measures with non-intrusive measures and technologies. | More advanced video cameras were installed, with more vantage points, and with a recording feature. |

Stay tuned for more information from AFFP. They are already embarking on another audit: How can Itasca County create a deterrence from the court environment and proceedings being used as tool for ongoing battering?

For more information on this community’s experience with the Safety Audit, email info@praxisinternational.org.

Tool Highlights!

- Disparity-Focused Institutional Analysis Highlights: Key Tailoring Approaches

- SVJI@MNCASA recently released What Do Sexual Assault Cases Look Like in Our Community? A SART Coordinator’s Guidebook for Case File Review as a step-by-step guide that leads SART coordinators through the SVJI process of reviewing law enforcement case files.

- Check out the recently updated interactive Institutional Analysis impact map!

- Recent webinar recordings

- Reduce Unintended Consequences and Disparity of Impact, March 2017

- Supporting Safety Together: Assessing Child Protective Services Response to Battering, February 2017

- Need to Re-Invigorate Your Coordinated Community Response to Violence Against Women? January 2017

- Assessing for Core Practices in Criminal Justice System Response to Domestic Violence: Using the Best Practice Assessment Guides to Analyze 911 & Patrol, October 2016

Dear Praxis: Who conducts a Safety and Accountability Audit?

Dear Praxis: Who conducts a Safety and Accountability Audit?

We provide individual consultation to you as you prepare for, plan, and conduct your community assessment. Email info@praxisinternational.org to learn more.

Dear Praxis,

Who conducts a Safety and Accountability Audit? I have heard some different perspectives on whether it’s someone from outside of our community or whether its someone locally. Please advise.

Dear Change Seeker,

First, the Safety and Accountability Audit is designed as a collaborative process for local interdisciplinary teams to analyze and enhance their response to violence against women, so it’s a team that conducts an audit! Watch this 15-minute video on pulling together a team to conduct a Domestic Violence Best Practice Assessment. Much of the content in this video applies to a Safety Audit, too. Key points from the video:

The size of the local interdisciplinary team that conducts an audit or assessment depends on the size of your jurisdiction and the scope and focus of your audit. Some are small (3-5 people), some are large (15-20 people), and we have seen every size in-between.

Who makes up the local interdisciplinary team also depends on the scope and focus of your audit. Representatives of the discipline being assessed must be included. These representatives will be the most familiar with how their work is organized, and the policies and protocols that apply at each particular point of intervention. Participation by experienced practitioners will ensure the thoroughness and accuracy of the findings, and will enhance the credibility of the recommendations, as well as build commitment to implementing changes in their own agency. For example, if you are analyzing your criminal legal system response to sexual assault, you would definitely include representation from community-based advocacy programs, law enforcement (investigators and supervisors), prosecution, victim-witness advocates, and sexual assault nurse examiners. If you are analyzing your child protection system’s response to the co-occurrence of battering and child maltreatment, your team would likely include front-line child protection workers and supervisors, community-based battered women’s advocates, guardians ad litem, and family law attorneys.

Team members participate in mapping, observing, interviewing, and text analysis, as determined by the scope and organization of the Audit. They also meet as a group to discuss the Audit findings, recommend changes in policy, procedure, and training, and, strategize on how to implement recommended changes. Some team members go on to help implement, monitor, and evaluate the changes over time. Team members ideally should:

- Have a deep knowledge of the system within which they work

- Be open, non-defensive, non-judgmental

- Be committed to improving outcomes in cases involving violence against women

- Have connections to decision-makers to support implementation of audit findings.

So it takes a team to conduct an audit. However, the Coordinator is the glue that holds the whole process together, and manages all of the details of the work of conducting an audit. In many communities, the coordinator has been someone from the community-based advocacy program. Often this is an advocate with extensive experience with the system being analyzed. Community-based advocates are uniquely positioned to keep victims’ experiences and needs central to the assessment. Without that anchor, it is far too easy for practitioners working in the criminal legal system to focus on the needs and efficiency of that system. If not the audit coordinator, community-based advocates are crucial leaders on your team.

Many communities have successfully used others from their community to coordinate the process, as well. For example, the coordinator may be someone working in the agency being analyzed, such as 911 or law enforcement. Gathering the agency’s policies and files for review can be expedited when the coordinator is from that agency. This structure can also streamline the implementation of policy and practice changes recommended by the audit team.

A few communities have contracted with someone outside of their community or system. For example, one community contracted with a local university for a professor to coordinate the process. Another community contracted with a private consultant with expertise in violence against women and some local knowledge of the system being analyzed. This worked for teams where an outside, unbiased perspective was preferred.

Finally, sometimes communities seek outside consultation from national experts on the audit methodology and/or the content area being analyzed. Through a grant from the Office on Violence Against Women, some level of free consultation, guidance, and support is available from Praxis to communities engaging in an audit or assessment. For some communities, this assistance is more limited than what they need for their projects, and they hire a consultant from Praxis to provide more intensive support. Consultants can do full project planning, strategizing, meeting facilitation, and data analysis to helping articulate the findings and recommendations. As you’d expect, the better trained and more skilled your Coordinator, the less consulting support you’ll need. Review our webinar archive for resources to prepare your coordinator and team.

Sincerely,

Praxis Institutional Analysis Team

Distinctive applications

Institutional Ethnography (IE), Nursing Work and Hospital Reform: IE’s Cautionary Analysis, by Janet M. Rankin & Marie Campbell

Write Like a Visual Artist: Tracing artists’ work in Canada’s textually mediated art world, by Janna Klostermann

Investigating the social relations of human service provision: Institutional ethnography and activism, by Naomi Nichols

[June 2017]