The Rural Digest

An e-newsletter featuring the best and promising practices, research, and training and assistance to support rural efforts to end violence against women. Note: current grantees of OVW’s Rural Program will receive email notification of these newsletters. If you think you are not on this email list, please email us at info@praxisinternational.org to let us know and we’ll get you added to our list.

Praxis offers support to implement your rural coordinated interagency responses to violence against women, and to strengthen individual and institutional advocacy on behalf of survivors. The Rural Digest features replicable, time-tested intervention models, social change-advocacy strategies, and tools, templates, and materials. Access our centralized rural clearinghouse to connect with rural-specific training, TA, information, strategies, research, and with your peers (the list of current rural grantees have been updated to include FY16 Rural Grantees).

Rural life: connections, trust, and privacy

Implement now! Advocacy strategies: getting to know your community

Implement now! CCR strategies: planning for and leading change

You asked…we answered: resources for working with faith communities

New tools

Uniquely rural resources

Rural life: connections, trust, and privacy*

Collaborative contribution by Praxis International and Victim Rights Law Center

Everyone is related to each other – literally in some smaller communities. They are related to the victims and survivors – so there is a perceived lack of confidentiality, because there is a lack of confidentiality.

– Director of a rural community-based advocacy program

Sometimes we have had an abuser’s mother in our support group for their own experiences with violence. And then we’ve had a woman in the group at the same time where the first victim’s son is beating her. It gets complicated to manage those pieces.

– Rural community-based advocate

We served a young mother, she is married, there has been a history of domestic violence and she needs legal issues solved as well as counseling. Her father was with a woman who we served recently. That woman drove by and saw her former intimate partner’s daughter’s truck and she called and asked, “What is she there for?”. She said it was a conflict of interest.

– Director of a rural community-based advocacy program

Navigating the complex requirements and best practices for protecting rural survivors’ privacy rights related to confidentiality, privilege, and mandatory reporting can be very tricky in rural communities. The reality in rural communities that “everybody knows everybody” shapes the work of rural programs in distinct ways that are not typically experienced to the same degree by urban counterparts. While lack of anonymity in rural communities can be an advantage in addressing violence against women – family and friends can “watch out for each other” and readily provide support – it mostly creates serious disadvantages for victims. Retribution can be directed toward them, by the abuser or the abuser’s family, for not keeping silent and protecting the status or reputation of the abuser and their family. Agency practitioners often have relationships with each other outside of their professional roles that can impact how they respond.

Navigating the complex requirements and best practices for protecting rural survivors’ privacy rights related to confidentiality, privilege, and mandatory reporting can be very tricky in rural communities. The reality in rural communities that “everybody knows everybody” shapes the work of rural programs in distinct ways that are not typically experienced to the same degree by urban counterparts. While lack of anonymity in rural communities can be an advantage in addressing violence against women – family and friends can “watch out for each other” and readily provide support – it mostly creates serious disadvantages for victims. Retribution can be directed toward them, by the abuser or the abuser’s family, for not keeping silent and protecting the status or reputation of the abuser and their family. Agency practitioners often have relationships with each other outside of their professional roles that can impact how they respond.

Victims are often visible when they access advocacy or when systems become involved, and word travels quickly. Their cars are seen parked near agencies; their cases are scrutinized when making referrals or by coordinated community response teams; their stories are shared with community members in support groups; and soon enough everyone knows their business. This is the messy, inconvenient, challenging context of providing rural victim services. And yet, victim privacy must be protected. Confidentiality is a cornerstone of successful victim advocacy. Survivor safety, autonomy, and recovery, along with a community’s trust in a victim services program, depend on protecting that privacy. While this may be particularly challenging in rural communities, it is, indeed, crucial to their safety and autonomy as well as to their relationship with you and your services. Here are several points to consider:

- Victim Safety: Victims’ lives may depend on their secrets being kept. If abusers know where to find them and their children. Or that they are thinking of leaving. Or that they shared details about their relationship. This information can increase the danger they face. Advocates cannot effectively safety plan if they are not trusted to keep information private.

- Victim Autonomy: Victim-centered advocacy requires that victims get to determine what happens with their lives, their information, and, therefore, the services they receive. Victims will reestablish autonomy as they regain control of their lives and their narrative, including control of who knows their secrets. Disclosure of confidential information can derail a victims’ control of:

- custody, child welfare and criminal cases;

- employment, school, or housing; and

- reputation and relationships in the community.

- Victim Recovery: When information a victim expects will be kept private is shared, their recovery stalls. They will likely be re-traumatized. Their mental or physical health may be affected. Support needed from their community to heal is undermined. Victims are more likely to continue to access advocacy and services if they trust that their information is safe.

- Community Trust: People in communities know who keeps secrets and who reveals them. Victims in need of help will not come to a service provider with sensitive information if that service provider is known for divulging confidential information.

Here are some key tips for advocacy programs to preserve confidentiality, maintain privilege, and ensure integrity and trust in relationships with victims:

- Know local, state, tribal, and federal laws that govern confidentiality, privilege, and information-sharing:

- Know when you are mandated to report and disclose this to victims during your first meeting with them. If you don’t know your mandatory reporting obligations, the VRLC’s jurisdiction specific privacy cards are a good place to start. (Request the card for your jurisdiction – in Spanish or English – at PrivacyTA@victimrights.org).

- Don’t promise more than you can deliver with keeping information private.

- Make sure you know your collaborative partners’ ability to keep information private before you make a referral or discuss a case.

- Make sure technology and remote services you use are confidential.

- Vary meeting locations and parking, and don’t discuss cases in public.

- Use appropriate interpreters and translators.

- Have protocols in place to protect minors’ privacy.

- Develop releases of information that are:

- Written

- Informed

- Time-limited

- Discipline-specific

- Available in all languages spoken in your community

Resources on confidentiality, privacy, and privilege:

- Listen to a recent rural webinar of the Victim Rights Law Center Privacy Rights Project that provides tools, resources, training, outreach, and education to identify and protect survivors’ privacy rights, including:

- Developing Program Policy on Staff Use of Personal and Remote Devices

- A resource library with materials on specific populations including campus sexual assault survivors, elders, farmworkers, individuals experiencing homelessness, and male survivors.

- Confidentiality: An Advocate’s Guide, by Battered Women’s Justice Project

- Access a substantial resource list on issues related to privacy, including social media, address confidentiality, and digital safety.

- Please contact the Victim Rights Law Center with any privacy questions at PrivacyTA@victimrights.org.

*Connections and trust is one of several themes identified in Enhancing Technical Assistance to Rural Program Grantees Responding to Violence Against Women: A Report to the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, a report by Praxis available about your collective training and TA needs as rural grantees.

Implement now! Advocacy strategies: getting to know your community

By Praxis International

In 2005, Praxis invited a small group of advocates from rural communities to spend a weekend talking about their successes, and challenges, in organizing an end to violence against women in their communities. All of the women who came to talk with us had organized and provided services for battered women in rural settings—some of them for more than 30 years. We wanted to know what they could tell us about their work that would help others just starting out. Below is an excerpt of From the Ground Up: Strategies for Organizing in Rural Communities, a discussion guide and videos that were produced from those conversations, that highlights what we captured from them about starting a program from scratch…It’s amazing how relevant is all is 12 years later, even for established programs…

In 2005, Praxis invited a small group of advocates from rural communities to spend a weekend talking about their successes, and challenges, in organizing an end to violence against women in their communities. All of the women who came to talk with us had organized and provided services for battered women in rural settings—some of them for more than 30 years. We wanted to know what they could tell us about their work that would help others just starting out. Below is an excerpt of From the Ground Up: Strategies for Organizing in Rural Communities, a discussion guide and videos that were produced from those conversations, that highlights what we captured from them about starting a program from scratch…It’s amazing how relevant is all is 12 years later, even for established programs…

More than thirty years ago, Debbie Bresette invited a small group of women to gather at her kitchen table in Bastrop, Texas, to talk about victims of domestic violence and how to help them. Soon they made an arrangement with the town’s trash collectors to hand out a phone number to women who seemed to be in trouble. That was the beginning of the Family Crisis Center that still serves Texas women today. At about the same time in Minnesota, Jo Sullivan was astonished to find in her kitchen a screaming neighbor with a newly broken nose, and she rallied other neighbors to get the woman to safety. That was the beginning of Range Women’s Advocates, still serving 21 Minnesota communities. The Family Crisis Center and Range Women’s Advocates were kitchen table enterprises, patched together over cups of good strong coffee to meet the immediate needs of women who lived next door or just down the road.

Starting a domestic violence and/or sexual assault program today is a different matter. There are precedents and training manuals and conferences and grants of public money to help you. These days you can start with an idea—to provide safety for victims, to end violence in your community, to promote wellness in families—even if you’re not personally acquainted with the woman next door, the one with the broken nose.

Getting started is different now, but not necessarily easier. Faced with a battered woman, bleeding, in your own kitchen, you’d figure out pretty quickly what to do next. But beginning with an idea, a concept, a desire to help, a lot of energy, and a raft of good will—well, what exactly should you do?

To figure that out, you have to know your own community—the people, the institutions, the culture, the beliefs and aspirations. Small towns tend to be more homogeneous than cities. People in rural communities often think and act along parallel lines, to vote for the same party, to practice the same faith—especially if they share a common ethnic background, like the African-Americans of the Mississippi Delta, the Native Alaskans of Alakaket or Sitka, or the Slavs or Finns or Germans of the Iron Range in Minnesota. In a city, you’re likely to meet all sorts of people with all sorts of beliefs, but in a rural community the limits of what is considered acceptable thought and behavior can be narrower. And the minute you suggest the slightest change, you’ll be seen as the outsider spouting outside ideas.

That’s why it’s your job first to get to know this community from the inside. How do people here feel about things in general, and violence against women in particular? What are they already doing about it? Who are the responsible individuals and agencies? How do they work, and why do they work that way? Who’s working together and who’s not? And then the crucial questions for your program: What’s needed here? What works?

Getting to know your community is no small job. Tootie Welker, previous Executive Director of the Sanders County Coalition for Families, told us that when their program was getting underway, she spent the first full year driving around the county, meeting and talking to people, learning how they thought and how they did their jobs, getting them used to her, building trust, figuring out how to work together. Even if you’re working in your own hometown, you’ll find some people and agencies completely new to you. But in the end, if you’ve done this job right, you’ll know the community—its operations, its relationships, its beliefs and values—better than some people who have lived there all their lives.

To be able to work effectively in the community, you also have to examine yourself and the limits of your learning. And when it comes to providing leadership in a community, Jennifer Gibson-Snyder offers an important reminder: “We may know a few things about violence and how it works and kind of, sort of, how to provide services for victims, but we don’t know everything. And we don’t know how it works in other people’s communities… As an outsider organizing, I think that the first number one thing is to be humble.”

The women who participated in the Praxis conversations unanimously agreed that a good organizer meets people “where they are.” That is, the organizer identifies a common interest—What’s needed here?—as a baseline, a starting point from which to go forward together. In the end, you want your program to be a good citizen. You want your work to be not just accepted but valued by the community and nurtured, supported, protected, honored. That’s the goal. But the end is in the beginning—not in what you start, but in how you do it. The long process of getting to know your community and yourself is absolutely essential to launching a successful program. Wanting to help is not good enough. First you have to want to learn.

To read more about what this group of rural advocates and leaders shared with us, download the discussion guide and watch any of the following videos:

Pt 1: Where is Rural?

Pt 2: Starting from Scratch

Pt 3: How Did You Learn to Organize?

Pt 4: Educating Your Community

Pt 5: Being Effective, Being Yourself

Implement now! CCR Strategies: planning for and leading change

By Praxis International

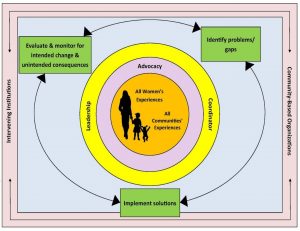

What are we leading? What is the work of coordinating an interagency response or “CCR”? A CCR is the collective act of ensuring that institutions intervening in violence against women (1) centralize safety and well-being for victims/survivors, and (2) hold perpetrators accountable while offering opportunities to change. An effective CCR, centered around the experiences of all survivors in our community, has three overarching tasks:

- Identify problems/gaps between what victims/survivors of violence against women need and what institutions provide

- Implement solutions by building the necessary changes into how institutions intervene (i.e., change how cases are processed) while anticipating and trying to avoid harmful unintended consequences

- Evaluate and monitor for intended change & unintended consequences

CCRs continue this process as new problems and gaps surface. This kind of change is not a linear process with a finite end point. It is continuous and it involves leadership at many levels: advocates, practitioners, agency administrators and decision-makers, and women and survivors. A CCR is fundamentally a commitment to a process of ongoing interagency problem solving and accountability to end violence against women. Use the following worksheet to help explore how you might prepare for and approach agencies about a gap in your community you would like to see addressed.

Leading and coordinating interagency change work is institutional advocacy in action. It is easy in our everyday work to focus on what an individual worker has done or not done on behalf of women who have been battered and raped. When we see the harm caused by individual perpetrators and by the official response, we often see the problem as the attitude of the individual practitioner…“Bob [the detective] just doesn’t care about rape victims; he makes them describe what happened again and again”. Focusing on an individual, however, does little for systemic change. If Bob is replaced by Tim or Sue, practices in the police department and the court administrator’s office are unlikely to change.

To help keep our focus on systemic, institutional practices, we have developed 4 Golden Rules of Institutional Advocacy: Leading an Effective Interagency Response to Violence against Women (learn more about these Golden Rules through our online learning course, Essential Skills in Coordinating Your Community Response to Battering: An E-Learning Course for CCR Coordinators). We guarantee that if you ground your interagency leadership and coordination in these four rules that you will make a difference in women’s lives and the ways that community systems intervene in violence against women.

To help keep our focus on systemic, institutional practices, we have developed 4 Golden Rules of Institutional Advocacy: Leading an Effective Interagency Response to Violence against Women (learn more about these Golden Rules through our online learning course, Essential Skills in Coordinating Your Community Response to Battering: An E-Learning Course for CCR Coordinators). We guarantee that if you ground your interagency leadership and coordination in these four rules that you will make a difference in women’s lives and the ways that community systems intervene in violence against women.

#1: Centralize victim safety, well-being, and autonomy:

- Know the scope and scale of violence against women in your community (see our data gathering document for what information to collect and how to collect it).

- Focus on changing the system to improve outcomes in the lives of victims, not just making the system run more effectively from the agency’s perspective.

- Advocates play a key role in leading interagency work in ways that focus on the needs, safety, and well-being of women/survivors.

#2: Develop a strong knowledge base:

- Do not assume anecdotes, advice from individuals, personal experience, statistics, etc. show the whole picture.

- Research the issues and know:

- Circumstances victims face.

- Institutional responses and their outcomes.

- How workers are organized to act on cases.

- Institutional assumptions, theories, and concepts.

#3 Use a systemic and social change analysis:

- Always focus on case processing and weaknesses in case processing—not individuals—that contribute to poor outcomes for victims/survivors.

- Know and recognize how institutions standardize their responses.

#4 Use a model of constructive engagement:

- Be respectful; problem-solving rarely works in an atmosphere of criticism or personal attack.

- Assume that practitioners can and will help.

- Build relationships and trust. Work with people as colleagues.

- Remember that there are consequences for survivors of using a judgmental approach with practitioners.

- Avoid backing a practitioner or agency into a corner.

- Remain solution-oriented.

- Bring all points of view into the discussion.

- As a leader, facilitate analysis and problem-solving. Avoid acting as a gatekeeper—or a hero.

Sometimes leading change means facilitating and managing large groups of people to “get on the same page”. More frequently, however, it involves small ad hoc committees or even just two people to work on a given problem. Regardless, following the golden rules will be crucial in your approach with agencies to develop effective interventions.

Resources on planning for and leading institutional change efforts

- Sexual Assault Response Teams Toolkit, by Office of Victims of Crime

- Collaborative response to sexual assault, by Sexual Violence Justice Institute @ Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault

- A Coordinated Community Response to Domestic Violence, by Ellen Pence and Martha McMahon, 1997

- A Guide to Becoming a Blueprint Community, by Praxis International

- Building a Coordinated Community Response to Domestic Violence Curriculum Package, by Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs and Praxis International

- Webinar archive

- Roles, Tasks, Responsibilities for CCR Coordinators, March 2017

- Leveraging Key Features of Rural Life to Benefit CCR Efforts, December 2014

- Increasing Your Program Capacity for System’s Change, October 2014

- The Crucial Role of Community-based Advocates in Rural CCRs, May 2014

- Three Key Skills for Successful Interagency Leadership, January 2014

You asked…we answered: Recent questions from rural grantees

We provide individual consultation to you on organizing your community’s response to violence against women. Email info@praxisinternational.org or call us anytime with your questions. 651-699-8000

Hi Praxis – Can you direct me to the best resources for working with faith communities around violence against women?

Hi Praxis – Can you direct me to the best resources for working with faith communities around violence against women?

Our response

Faith communities play an important role in the lives of many women/survivors, who may turn to them for support, information, and spiritual connection. In rural areas, faith can be a central thread in the fabric of the community. It is essential that we, as advocacy programs, have strategies for meaningfully engaging with faith leaders to send messages of help and support to victims and accountability for offenders. How can we engage with faith communities to increase the support they provide to individual survivors? How can we engage with faith communities to send messages in the broader community that discourage violence against women? What resources exist that our faith communities can use without having to “reinvent the wheel”? There are several resources that can help…

Resources on organizing with and within faith-based communities

- Safe Havens Interfaith Partnership Against Domestic Violence

- FaithTrust Institute

- Blogs on domestic violence, sexual violence, sexual abuse by clergy, child abuse

- Jewish materials

- Muslim materials

- Christian materials

- Multifaith materials

New Tools

- Access the TA events calendar for all OVW TA provider events

- SVJI@MNCASA recently released new evaluation tools!

- What Do Sexual Assault Cases Look Like in Our Community? A SART Coordinator’s Guidebook for Case File Review as a step-by-step guide that leads SART coordinators through the SVJI process of reviewing law enforcement case files.

- Are We Making a Difference? Resources for Sexual Assault Response Teams assessing systems change

Uniquely Rural Resources, Approaches, and Information

Neighbor to Neighbor

Neighbor to Neighbor

Helps reduce social isolation for rural Kansas women by providing a space to socialize, eat free meals, complete chores like laundry, and learn skills like cooking and pain management.

Meeting the Need: Mobile Medical Begins Service in Rural Areas

Meeting the Need: Mobile Medical Begins Service in Rural Areas

Highlights a mobile medical service in rural areas of Oregon and Washington that provides medical, dental, mental health, and substance abuse services by scheduling and transporting health professionals to rural communities.

Prevention and Treatment of Substance Abuse in Rural Communities

Prevention and Treatment of Substance Abuse in Rural Communities

Webinar recording discusses the challenges and strategies in stemming the rate of substance abuse in rural communities. Introduces the Rural Prevention and Treatment of Substance Abuse Toolkit, designed to help communities implement substance abuse programs. Presents several examples of state level programs focused on increasing access to naloxone and training for first responders to recognize and prevent overdoses.

In Rural Wyoming, Cops Learn New Skills To Deal With Mental Health Crises

In Rural Wyoming, Cops Learn New Skills To Deal With Mental Health Crises

Describes the Crisis Intervention Training being used in Wyoming and how it is preparing law enforcement officials for mental health crises since they are often the first emergency personnel to a scene of such a crisis, especially in rural areas.

Income Inequality: A Growing Threat to Eliminating Rural Child Poverty

Income Inequality: A Growing Threat to Eliminating Rural Child Poverty

A new USDA Economic Research Service report shows that while there are overall improvements in the rate of rural child poverty, the issue of income inequality, a contributing factor, is growing and needs to be addressed.

This project is supported by Grant No. 2015-TA-AX-K057 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Justice.

[September 2017]