The Rural Digest

An e-newsletter featuring the best and promising practices, research, and training and assistance to support rural efforts to end violence against women. Note: current grantees of OVW’s Rural Program will receive email notification of these newsletters. If you think you are not on this email list, please email us now to let us know and we’ll get you added to our list.

Praxis offers support to implement your rural coordinated interagency responses to violence against women, and to strengthen individual and institutional advocacy on behalf of survivors. The Rural Digest features replicable, time-tested intervention models, social change-advocacy strategies, and tools, templates, and materials. Access our centralized rural clearinghouse to connect with rural-specific training, TA, information, strategies, research, and with your peers (the list of current rural grantees have been updated to include FY16 Rural Grantees).

Rural life: expertise at “making do”

Implement now! Advocacy strategies: building the case for systems’ change

Implement now! CCR strategies: a conversation about false reporting

You asked…we answered: CCR best practices related to immigrant survivors

Upcoming training and available support

Uniquely rural resources

Rural life: expertise at “making do” *

Rural life: expertise at “making do” *

By Maren Woods, Program Manager, Praxis Rural Technical Assistance Project

By Maren Woods, Program Manager, Praxis Rural Technical Assistance Project

Rural poverty has long been a reality, both in terms of income and social supports for families. Rural communities have historically been creative at managing scarce resources, but there is a limit to making do – beyond a certain point, limited resources mean significant barriers to safety. Particularly when resources are needed to fill significant voids for transportation, housing, health care, and language access for survivors.

Further, rural advocacy programs provide services in areas of enormous geographical distance with uncertain resources. Some programs rely solely on grant funding to provide basic transportation for survivors to access community resources, services, and attend court hearings. Connecting with one survivor can mean driving 200 miles round-trip in a day. Survivors may not have cars to transport themselves and may not want to ask family or friends for help. Many rural communities have no public transportation or a shuttle service run through a senior center only operates on Saturdays.

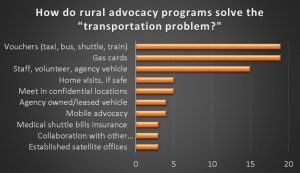

Advocacy programs offer transportation support to help survivors access important resources. Many bring support to survivors, in their homes or communities. Most programs do both. Some leverage other community resources or create uniquely rural approaches to solving the transportation problem. We recently asked you how you solve the “transportation problem” in your rural communities…here’s how you responded (22 total responses):

Supporting survivors to get to where they need to go

There are numerous ways advocacy programs get survivors where they need to go. Programs offer tokens, passes, vouchers, or automatic billing for transportation such as busses, shuttles, and taxi services. A rural advocate reported helping a survivor learn how to navigate public transportation by riding the local bus system with her. Several communities have no public transportation options, some have extremely limited bus routes and schedules, and one community’s taxi service is cost prohibitive for most victims. One program shared these problems with the taxi service in their community:

We consistently exceed our taxi budget…And some program participants have had unwanted interactions with taxi drivers – one told us that her abuser was a taxi driver for the company we use.

To solve these dilemmas, they reported unsafe interactions (without disclosing personal information) and the taxi company has fired those drivers. They have also shifted to a monthly taxi budget for each woman they advocate for, taking into consideration family size, medical needs, and distance. Women and their families can use the taxis for any reason, but need to stay within their monthly budget.

Gas vouchers are given to survivors for those who have their own vehicle or who can borrow one or get a ride from family or friends. Most programs offer these, as needed; one program offers a monthly generic gift card to survivors to purchase what is most needed.

Advocates and volunteers frequently use their own personal vehicles to support survivors with transportation. One program has insurance that protects staff’s personal vehicles.

Another program partners with a free, volunteer-based transportation program – typically for seniors and people with disabilities – to extend services to those experiencing domestic and sexual violence. Volunteer drivers in this program receive training on the dynamics of domestic and sexual violence.

Less common approaches include the use of agency-owned vehicles and Medicaid insurance coverage of transportation costs to medical and mental health appointments. One program reported that in rare circumstances they are able to provide funds for relocation costs (bus, plane, train).

Bringing support to survivors

There are numerous ways advocacy programs organize themselves to bring support to survivors. Advocates make home visits when they know the setting is safe and predictable. Several programs utilize mobile advocacy to bring services to women in more isolated parts of their service area. (See resource list below for more on home visits and mobile advocacy.) One community provides a confidential advocate in the community health center caravan that travels monthly to more isolated areas. Several programs meet with survivors in generally accessible, yet confidential, locations, such as churches, town offices, schools, hospitals, and libraries. (Could librarians make effective “on the spot” advocates?) Others meet with survivors in satellite offices scattered throughout their service area to create more accessible services.

Leveraging rural resources

As is common in rural communities, advocacy programs report partnering with other organizations to maximize accessibility and use of resources. Some make referrals to programs in neighboring counties, some meet staff from another shelter halfway. One program partners with the local chapter of the Salvation Army that gives $25 gas vouchers for job interviews or out-of-town medical appointments.

Creative rural strategies**

Several communities reported unique strategies for overcoming the transportation problem:

- Survivors with cars receive assistance with car insurance, car repair, and obtaining a driver’s licenses.

- Survivors appear by phone or skype for hearings with the courts and prosecuting attorney.

- The Sheriff’s Department provides transportation if the weather is poor or the circumstances are unsafe.

- One program provides free bicycles to survivors.

Interesting

Rural advocates provide resources and information over the phone as often as they can. But spotty internet and cell service are still real barriers. Amy Waldman, at the Massachusetts Rural Domestic and Sexual Violence Project of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, highlighted their leadership in the National TeleNursing Center (NTC) funded through the Office for Victims of Crime, which is the first national 24/7 sexual assault telemedicine resource for clinicians.

Through a video conferencing system, NTC links SANEs [sexual assault nurse examiners] to clinicians in rural and underserved areas to provide help in the examination process of a sexual assault victim following an assault. They also give guidance on how to collect forensic evidence that is used to prosecute the offenders. Their goal is to increase the confidence and competence of rural clinicians in performing a sexual assault examination, as well as to give quality support to the patients.

Excerpted from The Rural Health Information Hub

Regardless of where your program falls on the chart above, the approach you take can support a survivor beyond the basic need of a ride to get to a court date.

Keep us updated as you continue to innovate, translate other models to rural contexts, leverage partnerships with neighboring organizations and communities, and lean on your expertise in “making do” to meet the needs of survivors of violence against women. Contact Praxis to report your creative strategies or for referrals to any of the programs whose responses are included above: info@praxisinternational.org or 651-699-8000.

Resources on mobile advocacy and home visits:

- We’ll come to you… From Domestic Shelters

- Safety Planning Policy and Protocol and Home Visit Safety Policy from Home Free – Volunteers of America Oregon

- Intimate Partner Violence And Rural Public Health, from Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care, vol. 6, no. 1, Spring 2006, addresses home visits, confidentiality, role of public health nursing in domestic violence intervention, etc.

- Mobile Health Care for Homeless People: Using Vehicles to Extend Care, from National Health Care for the Homeless Council, May 2007

Other models that solve the transportation problem in rural communities:

- Transportation to Support Rural Healthcare – from the Rural Health Information Hub

- In Rural Areas, Mental Health Can Depend on Finding a Ride – from Oklahoma Watch

- Opioid crisis in rural areas may be tackled through telemedicine – from The Washington Post

- Meet Liberty, the Uber-like Service Built for Rural America – from Silicon Prairie News

*Expertise at “making do” is one of several themes identified in Enhancing Technical Assistance to Rural Program Grantees Responding to Violence Against Women: A Report to the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice, a report by Praxis available about your collective training and TA needs as rural grantees.

**Some of the strategies reported above are funded through sources other than the Office on Violence Against Women’s Rural Grant Program.

Implement now! Advocacy strategies: Building the Case for Systems Change

Implement now! Advocacy strategies: Building the Case for Systems Change

By Rose Thelen, Praxis Technical Assistance Partner, Gender Violence Institute

Individual advocacy informs institutional change advocacy

Advocacy programs are tireless in their efforts to assist as many survivors of gender-based violence as possible. In these efforts, every day, advocates hear stories about their experiences with systems, agencies, and/or businesses…good and bad.

These stories are a rich source of information that advocates can use to work for systems change on behalf of all women/survivors, and to enlist their involvement in addressing the systemic injustices they experience. In this way, advocates are experts about women’s/survivors’ experiences with systems. Yet stories without documentation only get us so far. Many advocacy programs are not set up to capture these stories as “data”. Quantitative and qualitative recordkeeping strategies help transform the stories into data that supports our case to advocate for change. This can also provide a concrete opportunity to invite women/survivors to help address the systemic problems they’ve experienced.

Building our case

You’ve heard from women that protection orders aren’t being enforced, but do you know the numbers? Is it just one officer who isn’t enforcing them? Or is it most that aren’t enforcing orders? The answer informs the approach to take…

You can constructively engage with systems, but if you bring only anecdotal information to the table, it can be readily dismissed. A simple tool and procedure to help capture this information and create the “science” that supports your requests (or demands) for change. Review, adapt, and implement the Procedure for Handling Institutional Response Concerns (see below) and related Tracking Form (see below) in your advocacy program to start tracking experiences with systems.

The procedure directs advocates, shelter workers, and volunteers to document the response in the Tracking Form. The form is then routed to the person within your agency designated to track and act on institutional problems (i.e., coordinator of your Coordinated Community Response, Sexual Assault Response Team, or multi-disciplinary team, institutional advocate, executive director, etc.). They decide whether to act immediately, because a problem is so egregious, or to bring it to the SART or CCR or the Chief of Police. Or they decide if it is something that does not require immediate attention but should be kept on file. Regardless, the form helps you track whether the problem is a pattern that needs to be addressed. The incident itself, and your efforts to address it, all become part of a paper trail to be used as you continue to pursue changes to improve outcomes for women/survivors.

Inviting women/survivors into the movement

This should not have happened to you. It has happened to other women and our program is working on changing this. Are you interested in helping?

It is important to design opportunities for victim involvement, such as meetings with decision-makers or focus groups, that enable women to be an integral part of systems change efforts. For many victims, well-being is increased by acting on the injustices they have experienced with system responses. When invited, many want to be involved in making change. The bottom of the Institutional Response Concerns Tracking Form directs advocates to invite women/survivors to be involved in addressing the matter with the system. In this way, we are creating opportunities for women/survivors to be a part of our efforts to make change. And then we have to be ready to act with them: we need to budget and fundraise in ways that allow us to compensate survivors for their time, contributions, and participation.

Story of action: After we had documented problems with a particular law enforcement agency’s response to battered women, I arranged a meeting with the Chief of Police. Five women and I went into the Chief’s office, and the women talked about officers who showed up after a domestic assault and did nothing, didn’t believe them, or buddied up with their abusers. They told the Chief that because of those experiences they would never call the police again. The women did not feel like law enforcement was a place they could go to for help. At the end of the meeting, the Chief was ashen, and determined to make sure that change happened in his department. The women, in turn, felt listened to and inspired by their success in making change happen.

– Rose Thelen, Gender Violence Institute

Never underestimate the power of a few determined women/survivors. It is, indeed, that spark that started our movement and will be the fuel to the flames of great change for years to come.

Resources for tracking and responding to institutional response concerns:

- Templates to support the process

o Institutional Response Concerns Procedure Template

o Institutional Response Concerns Tracking Form Template - Articles on systems change advocacy

o Making Social Change: Individual and Institutional Advocacy with Women Arrested for Domestic Violence, Martha McMahon and Ellen Pence

o Advocacy on Behalf of Battered Women, Ellen Pence

Resources to engage survivors in creating change:

- See Praxis’ community organizing exhibitions that documents rural grassroots organizing efforts (online exhibit)

- Tewa Women United – Empowering Women, Building Communities (15-minute video)

- Community Organizing in the Disability Rights Movement (10-minute video)

- Spark Movement: (website & blog) a girl-fueled, intergenerational activist organization working to ignite and foster an anti-racist, gender justice movement to end violence against women and girls, and to promote girls’ healthy sexuality, self-empowerment and well-being.

Implement now! A Conversation About Sexual Assault False Reporting

Implement now! A Conversation About Sexual Assault False Reporting

By Johnanna Ganz, Rural Projects Coordinator, Sexual Violence Justice Institute@Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault

Sexual assault is the only violent crime where the honesty of the victim is regularly questioned. Beliefs related to how a victim should have behaved before, during, and after the assault can cloud the facts of a case, and create road blocks to fair and full investigations as well as consideration for prosecution. Police and prosecution investigators commonly use aggressive interview techniques, typically saved for suspects, with victims of sexual assault. Some victims are threatened with a charge of false reporting. The threat of charging a victim has a chilling effect on a victim’s willingness to engage with law enforcement and can lead to recantations. This means that it is not uncommon for victims to withdraw their statements, because they do not feel supported or believed. This reality is common across the country and does not contribute to the pursuit of justice for victims, nor does it deter offenders.

Sexual assault is the only violent crime where the honesty of the victim is regularly questioned. Beliefs related to how a victim should have behaved before, during, and after the assault can cloud the facts of a case, and create road blocks to fair and full investigations as well as consideration for prosecution. Police and prosecution investigators commonly use aggressive interview techniques, typically saved for suspects, with victims of sexual assault. Some victims are threatened with a charge of false reporting. The threat of charging a victim has a chilling effect on a victim’s willingness to engage with law enforcement and can lead to recantations. This means that it is not uncommon for victims to withdraw their statements, because they do not feel supported or believed. This reality is common across the country and does not contribute to the pursuit of justice for victims, nor does it deter offenders.

Changing systems, practices, and beliefs about false reporting requires a willingness to have critical conversations and a capacity to have productive conflict within sexual assault response teams. These challenging conversations must include the core components of collaborative engagement, direct learning, reflective practice, and discussions about assumptions and biases. Through undertaking this difficult topic using these strategies, it becomes possible to reform practice, policy, and protocol. However, in order to get to those changes, teams first must have a shared understanding of the issue, an analysis of problematic practice, and an agreement to implement meaningful changes.

Sharing language to understand the issue

Clearly defining case classifications is an important first step to addressing false reporting in your community. A false report is when evidence from an investigation proves there was no crime; it is not when an investigation cannot prove an assault occurred. Other types of reports, from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report distinguishes between unfounded and baseless reports. Unfounded means after an investigation there is a determination that no crime occurred. Baseless is when an investigation finds a crime occurred but (1) doesn’t meet the legal definition or (2) there is insufficient information. Sometimes, when an investigation fails to prove a sexual assault occurred, they use unsubstantiated. Meet with your local law enforcement to learn more about the sexual assault crime classifications they use and the criteria for each classification.

Analyzing problematic practices

The “false report” category is often misused by law enforcement on sexual assault cases. This misuse is fueled by widely-held beliefs that people mischaracterize, exaggerate, or lie about being sexually assaulted—especially when the victim knows the perpetrator (non-stranger assault). People hold expectations of seeing severe injuries, presence of date-rape drugs like Rohypnol, evidence of “fighting back,” or weapons used. These, and other beliefs, are grounded in misinformation as well as dominant social ideas about gender and sexuality, rather than accurate data. In actuality, studies find 2-8% of reported rape cases involve a false report. This means that between 92-98% of sexual assault reports are victims seeking help and justice.

Problematic practice can show up when considering the characteristics of the assault. The dynamics and characteristics of non-stranger sexual assault cases as well as cases when a victim is voluntarily intoxicated confound investigations, because these cases rarely meet the biased beliefs our society holds about sexual violence. Victims in these cases rarely have physical injury, are less likely to seek medical/forensic exams, and experience coercion or manipulation that facilitates the assault. These characteristics lead to inaccurate judgments about whether a crime occurred, victim credibility, and case strength if sent to trial, which can lead to no investigation or under investigation. Analyzing these sorts of problematic practices and beliefs is important to changing ideas about false reporting.

Implementing meaningful changes within your system’s response

Systems across the country are changing their practices to reduce the intimidating nature of the sexual assault investigation, shatter myths and stereotypes of the sexual assault victim, and assess coding practices. SVJI@MNCASA, as well as many other organizations (see list below), can help your community explore these and other areas of criminal legal systems response to sexual assault crimes:

- Encourage and support efforts by law enforcement agencies to assess current coding practices, apply new guidelines and greater scrutiny to classifications. This includes an assessment of practices and revision of policies regarding recantations in sexual assault cases.

- Help your systems partners understand bias, review their classification process, and create standards of accountability for the investigation and classification processes.

- Train on how to use consistent application of definitions for classifying sexual assault data.

- Develop protocols for victim interviews that are based on the neurobiology of trauma, like the Forensic Experiential Trauma Interview, to increase the likelihood of accurate case coding.

- Revise protocols and agency practice to include a commitment from law enforcement to eliminate the practice of threatening to charge a victim with false reporting.

- Thoroughly investigate every case by treating each report as valid.

- Create specific investigative strategies for non-stranger sexual assault cases.

- Discourage law enforcement from asking victims to sign statements declining investigation of their case.

- Encourage regular referrals and involvement with community-based advocacy programs.

Resources for improving your system’s response to sexual assault crimes

- Connect with your local Sexual Assault State & Territory Coalitions

- Connect with Sexual Violence Justice Institute your rural-specific TA provider on Sexual Assault Response Teams

- Check out the Online Sexual Assault Training for Rural Law Enforcement Personnel

- National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations of Adults and Adolescents

- Check out the webinar recording library from AEquitas – The Prosecutors’ Resource on Violence Against Women

- EVAW International provides training, resources, and technical assistance to law enforcement in order to improve investigations and prosecutions of sexual assault cases

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center

You asked…we answered: Recent questions from rural grantees

You asked…we answered: Recent questions from rural grantees

We provide individual consultation to you on organizing your community’s response to violence against women. Email info@praxisinternational.org or call us anytime with your questions. 651-699-8000

September 2016

Any suggestions on where to look for best coordinated community response (CCR) practices related to cases involving immigrants?

Our response

There are several resources for CCRs to enhance their response to cases involving immigrants. The organizations listed below provide free individual support to you as you work to enhance your community’s response to immigrant survivors. Some of them will come to your community for free! Reach out to them directly for specific information.

Immigrant survivors’ rights and legal services

There is a critical need across the U.S. for local, available immigration legal services for victims of abuse, sexual assault and/or trafficking. With legal assistance to regularize immigration status, victims and survivors increase their choices: to leave, apply for a civil protection order, participate in the criminal court process, and/or take action in other ways that address the violence.

- Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. (CLINIC), a national resource center, assists advocates in becoming authorized immigration-law non-attorneys through a Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) recognition and accreditation program. The BIA program enhances a CCR’s ability to meet the dire needs of immigrant survivors.

- National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project has many resources related to a criminal legal system response to immigrant survivors. Some highlights:

o View webinar recordings, PSAs, and a set of roll-call training videos for law enforcement at NIWAP’s YouTube channel.

o Visit NIWAP’s web library to find resources on the legal rights of immigrant victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, trafficking, and other crimes.

Language access

Whether your CCR practitioners interact occasionally or daily with individuals with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), it is both necessary and useful to plan for and identify language resources. The Supreme Court has held that failing to take reasonable steps to ensure meaningful access for LEP persons is a form of national origin discrimination. Listen to Jan 2016’s rural webinar on implementing legal requirements of language access within your rural CCR and read Language Access in Rural Advocacy for an overview of what is required, and strategies for developing a language access plan. The following organizations are funded by OVW to support grantees on these issues:

- Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence offers training and support on federal and state laws, and policies on language access in civil and criminal courts, meeting the needs of culturally diverse victims/survivors with limited-English proficiency, improving language access policies and practices in organizations and systems, and model programs and practices for interpretation services.

- National Latin@ Network, a project of Casa de Esperanza, has a free downloadable toolkit on Increasing Language Access in the Courts.

Rural-Specific Training & Technical Assistance

Rural-Specific Training & Technical Assistance

Online Sexual Assault Training for Law Enforcement

The Criminal Justice Institute’s National Center for Rural Law Enforcement (NCRLE) has responded to the needs of rural law enforcement officers, both management and investigator, by offering two online courses ensuring sexual assault training is accessible to all rural law enforcement agencies regardless of manpower and budget limitations. The curriculum for Introduction to Sexual Assault for the Rural Executive Online provides rural law enforcement managers with the knowledge, skills, and resources for establishing a victim-centered response from their agency personnel. The Introduction to Sexual Assault for the Rural Investigator Online course is designed to enable rural officers to better understand the impact of sexual assault upon victims as well as ensure that each step in the investigation process is thoroughly conducted to apprehend the offender. Access the online courses.

For more information, contact:

Mira Frosolono, Assistant Director – LEOC

Criminal Justice Institute

26 Corporate Hill Drive

Little Rock, AR 72205

501-570-8072

mafrosolono@cji.edu

Technical Assistance and Training on Organizing Faith Responses to Domestic Violence

You already know that faith leaders can play a unique and important role in helping victims. Learn how to strengthen those faith community partnerships and improve access to services for victims of sexual/domestic abuse and increase victims’ safety. Safe Havens has funding to provide technical assistance and training for rural advocates and faith leaders in 6 more communities over the next year. Learn more about Safe Havens’ rural work and about how to participate in our trainings.

For more information, contact:

Alyson Morse Katzman, Associate Director

Safe Havens Interfaith Partnership Against Domestic Violence

amkatzman@interfaithpartners.org

www.interfaithpartners.org

617-951-3980

Sexual Violence Justice Institute’s Save the Date for the National Institute for SART Leaders

When: Early May 2017

Where: Saint Paul/Minneapolis Minnesota

What Next: Look for registration early 2017

For more information, contact: Johnanna Ganz, Rural Projects Coordinator: jganz@mncasa.org

Cultivating Possibilities National Conference

The Resource Sharing Project is providing this exciting 2.5-day training in mid-March 2017. The conference will focus on enhancing sexual assault services exclusively for OVW Rural Grantees that are dual/multi-service agencies. This national conference will bring together rural peers from dual/multiservice advocacy agencies all around the country to discuss emerging issues and innovative strategies for providing services to rural sexual assault survivors. Participants will be able to choose from workshops and facilitated conversations with leaders in the anti-sexual assault movement. Together, we will identify the barriers in rural communities and build on our strengths to create meaningful solutions for dual/multiservice advocacy agencies. There are only 100 seats available for this conference. Each Rural Grant (lead grantee and sub-grantees combined) may send four attendees. For more information, contact: Leah Green at leah@iowacasa.org or 515-244-7424 or learn more.

OVW TA Provider Directories

- Access updated list (and downloadable directory) of rural-specific & rural-relevant TA providers

- Working on or near Tribal lands? Access the new directory of OVW-sponsored Tribal TA Providers and Tribal Coalition Services

- Access the searchable directory of all OVW TA Providers

- Access the OVW training events calendar NOTE: some of events listed on this calendar require approval from your OVW Program Manager if you are using or plan to use OVW training funds to attend.

Uniquely Rural Resources, Approaches, and Information

Uniquely Rural Resources, Approaches, and Information

New Rural Realities Blog from SVJI!

Sexual Violence Justice Institute’s Rural Technical Assistance Project brings people, knowledge, and resources together to develop real solutions for rural communities addressing sexual violence. SVJI takes a collaborative approach in creating tools, trainings, and conferences designed for rural spaces and tailored assistance to meet your community’s specific needs. Rural Realities blog is a space to reflect, connect, and share about the work of coordinated sexual assault responses with others doing similar work across the United States. Please contact Johnanna Ganz with any rural related needs or questions.

The Daily Yonder: Keep it Rural

The Daily Yonder, a daily multi-media source of rural news, commentary, research, and features has been published on the web since 2007 by the Center for Rural Strategies, a non-profit media organization based in Whitesburg, Kentucky, and Knoxville, Tennessee.

Finding Statistics and Data Related to Rural Health

This guide will help you locate and fairly and accurately use statistics and data to understand rural health needs and rural/urban disparities, communicate rural health needs, and inform decision-making related to service delivery and policy.

LGBT people in rural areas struggle to find good medical care – from CNN Health+

Medical-Legal Partnership of Southern Illinois is a combination of legal aid and healthcare with a mission to improve low-income patients’ situations by addressing their health harming legal needs, or social determinants of health. Attorneys and paralegals work with healthcare professionals to offer services to economically disadvantaged people in 7 impoverished rural Southern Illinois counties that are designated Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs).

Please provide feedback to info@praxisinternational.org.

This project is supported by Grant No. 2015-TA-AX-K057 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Justice.

[December 2016]